Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson in his directorial debut, premiered on the first day of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. In many ways, it was the perfect film to start off the festival because the documentary is a celebration of art and culture featuring some of the most talented artists of their time.

It’s a beautiful film, full of joy, that celebrates Black culture and music. Its existence is also a victory against white dominated media threatening to erase diverse stories. This film is about a monumental Black film festival stacked with premier musical talent that took place 50 years ago. Yet many of us have never even heard of it. For that reason alone, Summer of Soul is a must watch. Spoilers below!

THE STORY

The documentary tells the story of the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969, which took place the same summer as Woodstock. Indeed, the cultural festival has been labeled “Black Woodstock,” though the nickname feels reductive and reflects the efforts that those who coordinated the event had to take to try to get the festival the attention it deserves.

If you’re anything like me, you’ve never heard of the Harlem Cultural Festival. It might surprise you to learn that the festival took place over several weeks in the summer of ’69 and featured luminaries like Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone.

How could a groundbreaking film festival like this be erased from pop culture? Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, who directed this film, admitted that he had no knowledge that this incredible event even took place. Such is the insidiousness of a culture that doesn’t recognize, let alone celebrate, accomplishments of people of color.

The film walks audiences through the festival, highlighting numerous performances, interspersed with some of the cultural context of the time, as well as featuring several of the key individuals responsible for the festival’s execution. Stevie Wonder performs, then we learn about promoter and host Tony Lawrence, followed by some background on the fight for social justice during that time.

The primary focus are the performances, as they should be, considering almost anyone who wasn’t physically present in Harlem that summer would not have had the opportunity to see or feel what this festival was really like. From Sly and the Family Stone, to 5th Dimension to Sonny Sharrock and Hugh Masekela, this documentary faithfully transports viewers to the summer of ’69.

THE GOOD

For a festival that took place half a century ago and was promptly forgotten, the footage is shockingly clear and extensive. It’s no small stroke of serendipity that the festival organizers had the foresight to make sure that this festival was archived properly. Considering that cell phones, let alone camera phones, were nothing but a science fiction dream at that time, the fact that Thompson had so much incredible footage to work with is truly a gift.

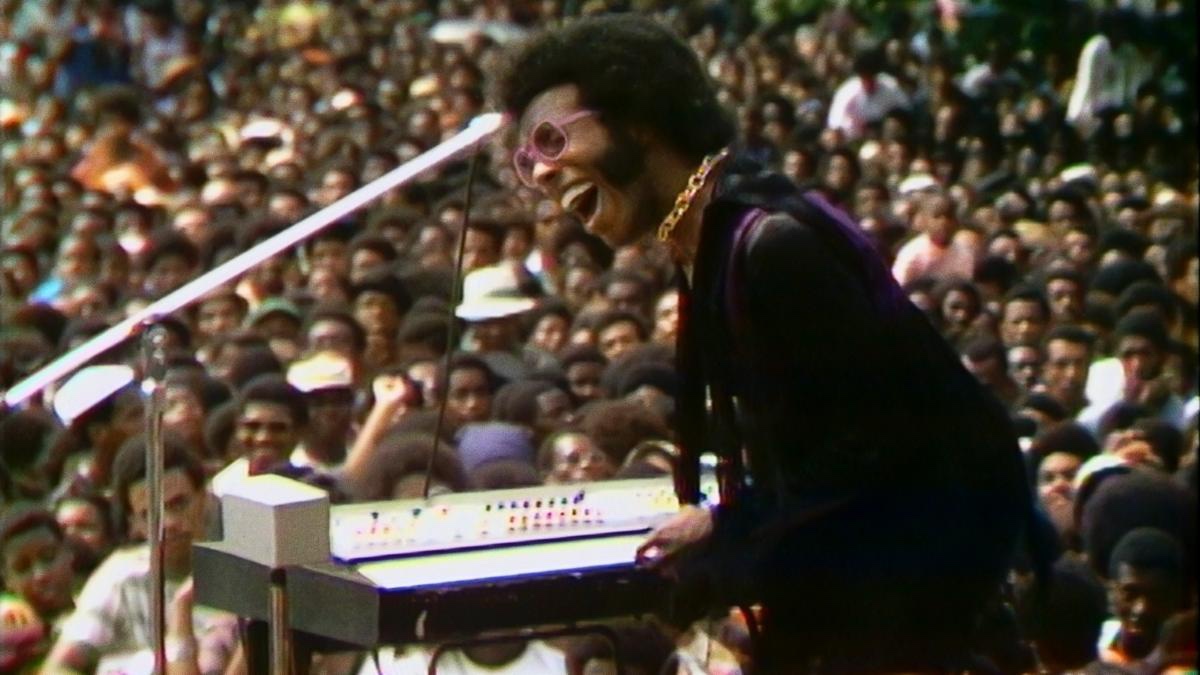

There’s a moment in the film when the back and forth of the storytelling and the voiceover simply stops while the incomparable Stevie Wonder performs on the keyboards. There are no words to properly describe the awe that comes with watching a genius in his prime using all of his considerable gifts. It’s a wondrous moment that truly reminds us how special the Harlem Cultural Festival was.

The historical context and recent interviews with both attendees and performers helps bring the narrative to life. The members of the 5th Dimension, who haven’t aged a day, glow both in their words and their presence on screen. It’s clear how much being a part of the festival meant to them and provides a glimpse into the impact it had on the community as a whole.

THE BAD

As wonderful as it is that we can watch these performances in their entirety, from a story-telling perspective, the narrative is lacking. There is some social and historical context provided, and important figures who contributed to the festival are profiled, but the film acts primarily as a recounting of the musical acts.

I would have appreciated more of a cultural context behind, during and after the festival. Tony Lawrence is identified as one of the primary individuals responsible for planning and executing the event. But his background is only briefly discussed and the work he put into the festival is hardly given the emphasis it likely deserves. Another intriguing figure was the Mayor of New York at that time, John V. Lindsey, who seemed to be a genuine ally for the Civil Rights movement and likely critical to the success of the festival. Yet, the film spends very little time with Lawrence, Lindsey or anyone else, seemingly over-eager to get to the next performance.

The end of the film, addressing the events following the festival, feels particularly abrupt. There’s an all too brief discussion about why that the festival was forgotten, that is unsatisfying and mystifying. For an event of this magnitude to have been erased, there needs to have been much more involved than a simple than a lack of popular interest. Instead, all we’re told is that efforts to sell the footage were unsuccessful and thus it was forgotten.

The cursory way in which the post-festival events were addressed left me wondering if those responsible for festival’s promotion wanted to make sure certain things were left forgotten.

THE POC-Y

Despite its weaknesses, Summer of Soul is a celebration of Black music, culture and perseverance. It’s a beautiful reminder of what can happen when a community and its leaders come together, and the joy that can be found even in the midst of difficulty. We all need that reminder.

RATING – 4/5 Pocky

Ron is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of POC Culture. He is a big believer in the power and impact of pop culture and the importance of representation in media.